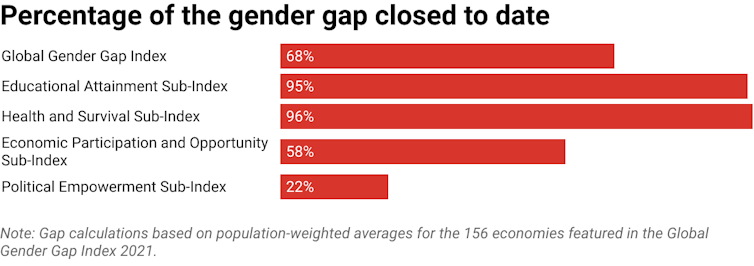

Across the world, women do not have the same opportunities as men. The 2020 Global Gender Gap Report from the World Economic Forum (WEF) revealed Australia came in at 44th in the Global Gender Gap Index 2020 rankings, slipping five places from the previous year. But wait, there’s more. The 2021 Global Gender Gap Index places Australia at number 50, a slip of another six places in 12 months.

And, at the current rate at which the gender inequality gap is being closed, it is now the case that it will take 135.6 years to close the gap worldwide. In 2020, the WEF had calculated gender parity would not be attained for 99.5 years. The 2020 report concluded:

“None of us will see gender parity in our lifetimes, and nor likely will many of our children.”

How is gender parity measured?

The key dimensions used to measure gender parity are:

- economic participation and opportunity

- educational attainment

- health and survival

- political empowerment.

As the reports point out, gender parity has a significant bearing on the extent to which societies can thrive. Fully deploying only half of the world’s available talent has an enormous impact on the growth, competitiveness and future readiness of businesses and economies across the world.

According to the 2021 report, COVID-19 caused the gender gap to widen as women left the workforce at a greater rate than men. Even among those who retained paid work, the report says, women took on more duties in childcare, housework and elder care, increasing the “double shift” of paid and unpaid work. Naturally enough, this has contributed to higher stress and lower productivity among women.

Australia remains equal first in the 2021 global rankings for educational attainment. So this is not an issue that might be tackled in Australia through improving education, including about inequality.

I propose that this is instead an issue of ingrained and systemic sexism in our country. How else can we explain the fact that Australian women get paid less than Australian men?

The 2020 report from the Australian Workplace Gender Equality Agency shows men take home, on average, $25,534 per year more than women. Contributing to this gap, the average full-time base salary across all industries and occupations is 15% less for women than for men.

Universities have failed to lead

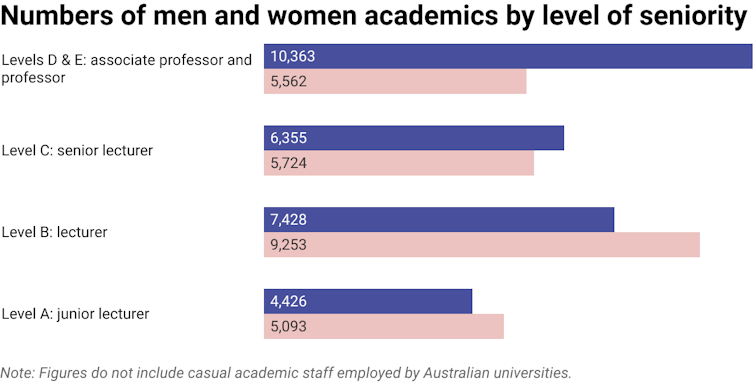

Given the woeful attitudes and behaviours towards women in the Australian parliament, one might hope for much-needed leadership from our intellectual hothouses – our universities. But not only have Australian universities not stepped forward to lead the change needed, they themselves perpetuate the problem. They have pay gaps of around the national average. Universities also continue to place men in the vast majority of leadership roles even where they have significant opportunity to do otherwise.

Universities – and other workplaces full of educated, insightful people – are well equipped to lead and make changes to enable gender equality. But they haven’t. And I haven’t seen any credible, funded, adequate plans for any workplace to do so in the near future.

Until recently, women have been too busy and tired doing most or all of the childcare, housework and elder care to have time to do much about the blatant inequality we all experience. But somehow, despite the extra burdens COVID-19 has placed on us, we’ve reached a tipping point. Perhaps the extremity of the inequality – laid bare during COVID-19 – has pushed us to the edge. Whatever the reason, we’ve somehow found the impetus to take action.

Women have waited long enough for things that “should” happen to happen. We’ve waited long enough for the people with power – mostly men – to do the right thing. We’ve followed the rules, done as we’ve been asked to do, helped out, worked hard, kept quiet and generally been very good girls.

This evidently hasn’t worked in our favour, nor in the favour of women worldwide. And so, for the sake of growth, competitiveness, society and the future readiness of businesses and economies, as well as our own advancement, we must take matters into our own hands.

Personally, I’m starting with the sector I have worked in for three decades – universities. Despite being home to some of the country’s brightest minds, we have some of the most sexist practices and embarrassing gender inequality figures a developed nation could have. The result is a workplace with 86% more male than female professors, as one example of many.

What can women do about this?

I’ve written a book calling on women (and enlightened men) to take action to improve gender inequality in Australian universities.

Among other suggestions, I recommend women reduce the volume and quality of the housework they do at home and at work. Office housework includes things like taking notes in meetings. Women are often expected to do this, no matter their role or level.

This uses up our valuable time and energy, as Facebook chief operating Officer Sheryl Sandberg and her colleague, university professor Adam Grant, point out in their humorously titled Madam CEO – Get Me a Coffee. And it is hard to make the killer point in a meeting when you are busy doing other things.

Reducing the volume and quality of housework undertaken will provide time, energy and goodwill that can be redirected to more fruitful ends. Redirecting their labour in this way will reduce support for the sexist structures that discriminate against women. The advice is relevant to those working in all industries.

Since posting on social media about this topic late in 2020, I’ve had hundreds of women who work in universities contact me about the contents of this book. The sentiment is a combination of fury about their current situation and steely determination to bring about change. Like the women who led, participated in and supported the 2021 marches, including a rally at the Australian parliament, women in universities also believe “enough is enough”.![]()

Marcia Devlin, Adjunct Professor, Victoria University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Adjunct Professor, Victoria University

-

This author does not have any more posts.